Atopia Training Game

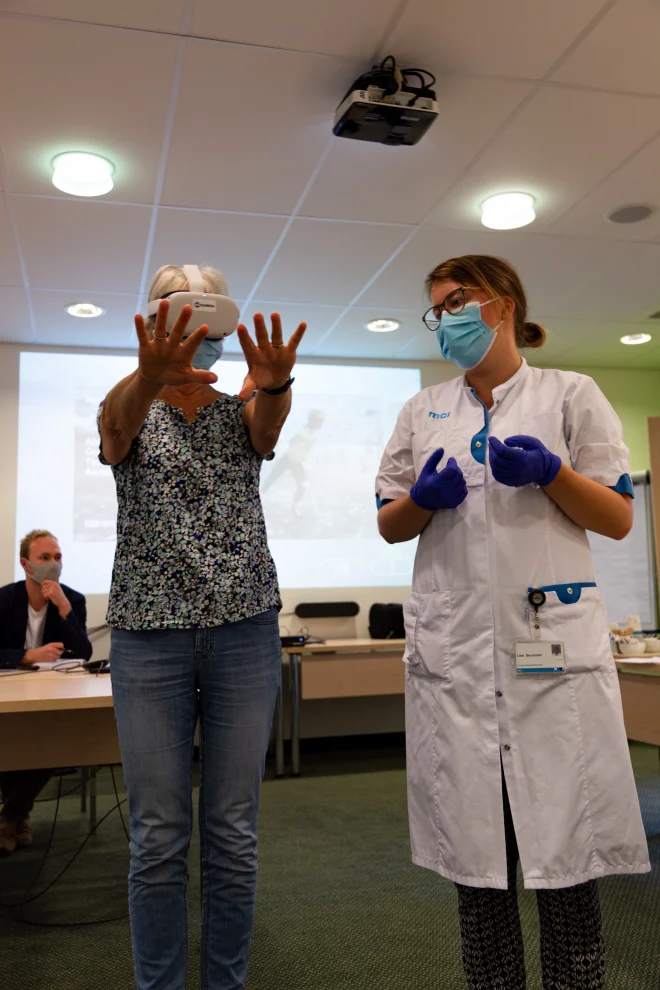

In addition to raising awareness, Van der Ham is also working on practical solutions. Earlier research showed that six weeks of training with navigation games can actually improve people’s navigation skills. Her research group developed a prototype game that allows players to practice navigating in a virtual environment. In collaboration with 8D, this game has now been further developed into a version suitable for use in hospitals and rehabilitation centers. A pilot will be conducted in 2025 and 2026 at three institutions: UMC Utrecht, Delft Rehabilitation Center, and De Hoogstraat Rehabilitation. “What’s great is that this game will become part of standard treatment,” says Van der Ham. “We’re not only looking at whether there’s measurable improvement, but also at how patients and therapists experience using the training game. That’s the only way to know whether an innovation truly has a chance to find its place in healthcare.”

“Everyone says technology should ease the burden on healthcare, but if the conditions don’t change, it never will.”

The implementation process comes with its share of challenges. Van der Ham explains: “You spend endless hours talking to committees and privacy officers, and in the end, nothing is allowed. It’s frustrating, but it also holds up a mirror to the system. Everyone says technology should ease the burden on healthcare, but if the conditions don’t change, it never will.”

That’s why Van der Ham looks beyond the pilot with the training game. Together with 8D and other project partners, she’s exploring ways to bring the challenges of implementation into public discussion. “We don’t just want to develop an intervention – we also want to expose the barriers that prevent such innovations from reaching everyday practice. By making those problems visible, we hope to work with researchers, healthcare professionals, and industry partners to find real solutions.”

The role of co-creation and design

Co-creation is a natural part of Van der Ham’s work. For instance, the first version of the training game featured a Greek mythology theme; it looked impressive, but feedback from the target group revealed several concerns. Van der Ham explains: “Therapists told us that people need to get lost virtually in a familiar setting, like a shopping street or a market. That makes it easier to translate what they learn in the game to the real world and to their own experiences.”

In these kinds of co-creation processes, a good designer can play a key role, says Van der Ham. “Designers ask practical and critical questions that researchers don’t always consider. They’ll simply say, ‘this won’t work in practice,’ or encourage you to bring prototypes to the target group early on. That may sound simple, but it adds tremendous value. It keeps projects grounded and prevents them from getting stuck in abstraction.”

Van der Ham experiences the collaboration with 8D as genuine and impact-driven. “You truly look at what’s needed, instead of just trying to sell a product or create something trendy. That means there’s much more focus on making effective choices, with an awareness of the system the innovation will become part of. You can really feel that difference.”

“Designers ask practical and critical questions that researchers don’t always think of – it keeps projects grounded and prevents them from getting lost in abstraction.”

Outlook

The public website on disorientation disorders (called ‘De Weg Kwijt’) was launched in September 2025. This site will gradually bring together all resources related to Atopia, from flyers to personal stories and exercises. One important next step is the launch of an experiential game. “How do you explain what Atopia is if you don’t have it yourself? That’s almost impossible. That’s why we’re developing a game that allows relatives and professionals to experience what it’s like to live with this condition.”

These initiatives are part of a broader social ambition. Van der Ham explains: “We need to recognize Atopia much earlier, especially in young people. And we need a healthcare system where innovations can find their place more quickly. I hope this project not only raises awareness of Atopia but also helps to spark systemic change.”

Want to participate in the research or stay up to date? Visit www.dewegkwijt.com